In the second conversation of our series on Commercial Law reform in Nigeria, we examine the constitutional issues that affect law reform.

In the second conversation of our series on Commercial Law reform in Nigeria, we examine the constitutional issues that affect law reform.

We also examine how these issues have impacted the reform of the Arbitration and Conciliation Act 2004.

Nigeria is a Federal Republic consisting of 36 States and a Federal Capital Territory.

There are three levels of government: the Federal, the State and Local Government and three arms of government: the Executive, Legislature and Judiciary. The federation is governed by a written constitution – the Constitution of the Federal Republic of Nigeria 1999 (‘1999 Constitution’) from which law-making powers are derived.

Constitutionally, laws can be made at both Federal and State levels. Accordingly, the 1999 constitution outlines law-making powers at each level of government. Law-making powers at the Federal level are vested in the National Assembly, the legislative arm of government. The National Assembly, comprising the Senate and House of Representatives, has the exclusive right to make laws in any matter set out in the Exclusive Legislative List set out in Part I of Schedule II of the 1999 Constitution. Law-making powers at the State level are vested in State Houses of Assembly, which can make laws on matters not included in the Exclusive Legislative List (Residual Matters) and those included in the Concurrent Legislative List set out in Part II of Schedule II of the 1999 Constitution. The law-making powers of Local Governments are usually stipulated in the laws that establish them. They have the powers to make laws on matters in Schedule IV of the 1999 Constitution and other matters provided in their enabling laws. Enactments made by the National Assembly are called ‘Acts’; by State Assemblies are called ‘Laws’; by the Local Government are called ‘Bye-laws’.

To appreciate some of the challenges of law reform in Nigeria, the origins of bills must be better understood.

Two types of bills may be placed before the National Assembly for passage into laws, namely an Executive Bill (Government Bill) and the Private Members’ Bill. Bills may originate either from the Senate or the House of Representatives but only one version will be passed and presented to the President for Assent. At the moment, it is typical to have competing bills on the same subject matter pass through each House of the National Assembly at the same time. The National Assembly Business Environment Roundtable (NASSBER), discussed in the last interview, was set up to act as a clearing house, amongst other things, for Bills. NASSBER leverages the technical grasp of relevant issues by the private sector to support the passage of the relevant bills. Through its activities, it deepens stakeholder engagement and collaboration with the National Assembly. Pursuant to these objectives, NASSBER participates in National Public Hearings and provides technical support to Standing Committees. For example, the Technical Advisory on CAMA provided to the Senate Committee on Trade & Investment Commission in January 2018.

In principle, Executive Bills would originate from the Nigerian Law Reform Commission, established by the Nigerian Law Reform Commission Act 2018 to, amongst other things, keep all Federal Laws under review with a view to their systematic, and progressive development in consonance with the prevailing norms of Nigerian society. In principle, the Nigerian Law Reform Commission would submit their bills to the Attorney General, for onward passage to the Federal Executive Council and then to the National Assembly as Executive Bills. One challenge that these bills face is the length and complexity of the procedure. Another is the political will. Executive Bills that are not passed in any legislative calendar need to be re-presented to the National Assembly. However, the new dispensation may have other priorities. Thus, the bill either floats without a sponsor or may be adopted as Private Members’ bill and followed up by such a party.

These constitutional and procedural issues have impeded the reform of the Arbitration and Conciliation Act, 2004, since the reform process started in 2007.

Questions have been raised about the power of States to make arbitration laws because arbitration is not mentioned expressly by the constitution, competing bills introduced to the National Assembly at various points, with NASSBER stepping in to evaluate both bills through its processes.

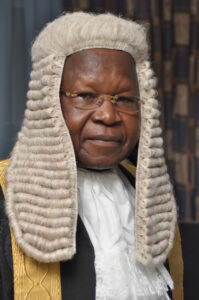

Some of these issues were reviewed by the ‘National Committee on the Reform and Harmonization of Arbitration and ADR Laws in Nigeria’ chaired by Hon. Dr J.Olakunle Orojo C.O.N., O.F.R., FCI.Arb.

The members of the Committee were:

(i) The Hon. Dr J. Olakunle Orojo C.O.N., O.F.R., FCI.Arb (Chairman)

(ii) H.E. Prince Bola A. Ajibola, K.B.E, S.A.N.

(iii) Chief (Mrs) Tinuade Oyekunle FCI.Arb

(iv) Mr. Muhammed Belo Adoke

(v) Mr. Paschal Madu

(vi) Dr. Paul Idornigie

(vii) Mr. Kelvin Nwosu

(viii) Mrs. Doyin Rhodes-Vivour FCI.Arb

(ix) Mr. Tony Amokeodo

(x) Mrs. Bakare (Director, Solicitors Department, Federal Ministry of Justice)

(xi) Mr. Dele Belgore, S.A.N. FCI.Arb

(xii) Mr Tunde Busari FCI. Arb

(xiii) Mr. Gbola Akinola

(xiv) Chief J. K. Gadzama S.A.N., MCI.Arb)

(xv) Babatunde J. Fagbohunlu MCI.Arb (Secretary to the Committee)

The terms of reference of the Orojo Committee were:

- To review Nigeria’s laws on arbitration and other ADR mechanisms with a view to proposing necessary reforms and to bring the laws in line with modern trends, and

- To perform such other acts as are necessary for the realization of the objective of giving Nigeria a modern law and procedure on alternative disputes resolution.

Watch the interview: (i)to learn more about the constitutional and procedural challenges of commercial law reform in Nigeria generally, and arbitration law reform more specifically, and (ii) to understand the reasons for the quest to modernise the legal framework of international commercial arbitration in Nigeria.